audacity

[ aw-das-i-tee ]

Boldness or daring, especially with confident disregard for rules, conventional thought, or other restrictions. Shameless or fearless effrontery / insolence.

The following is a tale of adventure and an enquiry into the landscapes of Psychotherapy that questions whether or not our current paradigm demands a radical update. When I ask fellow Psychotherapists the response is either an enthusiastic “YES!” or total bewilderment. What exactly an update might mean or look like nobody knows - nevertheless it does seem that change is desired within the field at large. In this brief article I’m interested in offering questions rather than answers and in provoking further debate. Here are a few to kick things off…

Is modern talking-therapy keeping up with the evolving realities of culture, society and our globalised psyches as they extend rapidly into unfathomed territories? Despite our efforts around intersectionality and inclusion, do contemporary frameworks still hold a vision of “normality” born out of white, patriarchal, middle class, heterosexual and European ideals? Does the popularity of plant medicines offer new possibilities or is this simply a way to enslave Nature in order to serve our psychological needs? Are we ignoring the advancements of AI at our peril? Do spiritual and esoteric approaches need to be untethered from their Psychoanalytic/Psychodynamic constraints in order to play a more central role across the board?

More questions to follow, but first a story…

Picture the scene; It’s July 1980. Beside yourself with excitement, you board a plane with twin propellers and cross the Irish Sea alone to spend the summer with your Grandmother in Belfast. You’re 11 years old. You enjoy all the concerned glances from other passengers and pretend you’re a secret agent and not the abandoned urchin they’re all imagining. Still, no one asks and no one interferes. You sit next to a middle-aged man in a tweed suit who drinks whiskey and chain-smokes Dunhills. Disembarking he points you in the direction of arrivals where you soon discover there’s no welcoming party and more importantly no Grandmother.

You retrieve your suitcase and board a freshly graffitied bus outside, bound for the city center. Its welcoming message in large white sprayed letters reads, “GO HOME!”. The afternoon is a blistering blue and beyond the grime streaked windows Belfast is revealing itself as the most dazzling place you’ve ever seen. It’s the height of the Troubles and a city rammed with roadblocks, army tanks, fear and division. Your Mother fled this place in the 1960s, ditching her accent on the way and arriving in London where pubs proudly exclaimed, “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs!”

Naturally, you’re oblivious to all this.

In the litter-strewn bus terminal, still no Grandmother. At the ticket office the friendly young woman hasn’t heard of her. This seems strange seeing as everyone in Ireland knows everyone else, or so you understood. Stranger still you’ve no telephone number to hand over, but the staff take her name and after about 10 minutes you’re told to wait over by the taxi rank, “Sure, y’ Granny’s on ‘er way so she is.”

You don’t give a second thought as to how on earth they managed to tracked her down. Instead you bask in a cacophony of sirens, car horns and the heady aromas of baking concrete and petrol fumes whilst feeling strangely at home. Posters plastered across the building opposite promoting gigs and record releases yell at you in neon pink; The Undertones, X-Ray Spex, The Clash, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Blondie, The Damned. An intoxicating world you long to be part of, if only you were older. These are the Autumn days of Punk but it all seems fresh to you.

A tan coloured taxi pulls up. Inside, your red-faced Grandmother with a head full of curlers crowded under a hair net is raging. Once you’re on the move she continues to bark her complaints at the driver and as she chews his ear off you relish the unfolding metropolis as it marches by.

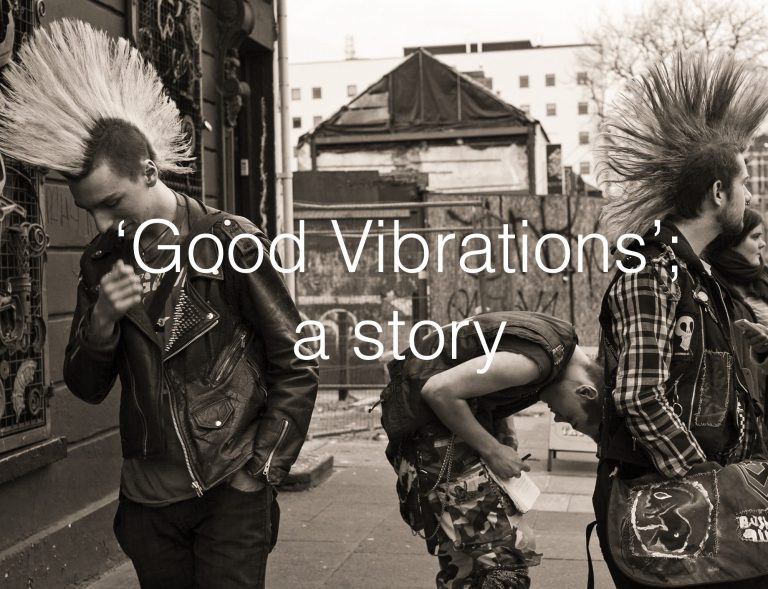

The next three weeks pass in a blaze of excitement and freedom. You roam the wilds of the city and go through checkpoints that turn the streets of the city centre into a forbidden labyrinth. You clamber over smouldering rubble and mess around in burnt out vehicles with local kids. Then, one Friday evening, from an upstairs window you watch as the neighbour’s teenage son and his friends gather on the pavement. A riot of pink and green crimped hair, safety pins, leather, hair glued into enormous spikes, torn and bleached denim. You’re mesmerised. A short while later they head off clutching cans of beer, cigarettes wedged behind pierced ears while tutting neighbours stand scowling from windows. You race downstairs and shove your feet into your new Converses but the laces are tangled, it’s taking too long and the horde is getting away. Creeping outside in your socks you duck behind blue hydrangeas until they pass the telephone box on the corner. Winding stealthily around parked cars you make it over to the red post box just as the menagerie are boarding a bus that belches clouds of diesel and then vanishes into the glittering mysteries of the evening.

By the time you return home to your life in the countryside the idea of the city as a veritable paradise full of hidden treasures has galvanised in your imagination. You’re too young for Punk but fortunately electro pop and the new romantics is just around the corner. You crimp your hair and make it to the goth clubs of Exeter followed by the rave scenes of Manchester before landing in London at the start of Brit Pop and The Young British Artists.

Four decades after that first trip you learn that a series of landmark Punk concerts took place at the Belfast Town Hall in the summer of 1980 as depicted in the 2013 film, ‘Good Vibrations’. From your life in 2023 you reminisce about the daring shock of Punk, the creative exuberance of the 1980s that followed and realise how much that summer of abandon inspired the rest of your life.

We need to stop there…

In Almut-Barbara Renger’s book ‘Oedipus and the Sphinx’ (2013), she makes a comparison between the Artist Jean Cocteau and his contemporary Sigmund Freud describing Cocteau’s art as bringing chaos to states of order whilst Freud brought order to states of chaos. As the inventor of Psychotherapy, Freud ingeniously created a new way, beyond psychiatric medicines, through which to examine our human experiences. He broke the mold at the time and in this way he was a true Punk.

In the mid 1970s Punk, created by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, disrupted music, fashion and art by offering radical possibilities. Born out of a reaction to post war bureaucracy, the struggles of the working class and dominant conservative values, it continues to influence much of our cultural lives today.

In such a carefully governed and safety-orientated field like Psychotherapy is there any need or in fact room for radical change - or is it simply fine as it is thanks very much? Whatever new ideas we do come up with don’t we still maintain the dynamic of expert (the one who knows) and patient (the one who doesn’t)? When taking on the identity of ‘Psychotherapist’ how much do we discard our own wild natures in favour of ‘being good’ and ‘being of service’ and how much does that impact our own well-being? Is re-invention actually an ethical necessity?

In Meg John Barker’s book ‘Re-writing the Rules’ (2013), they discuss the unspoken rules in society that most of us unconsciously follow. The book focuses on relationships and questions collective rules about sex, gender, attraction and love. I wonder what unchallenged rules we as therapists are following. Rules about ourselves. Rules about our clients. Rules about rules. What’s allowed, what isn’t? Who decides?

Punk is defined by individualism, expressing oneself freely and without apology. Artists demonstrate the true spirit of this with their willingness to leap into the unknown, embrace chaos and break rules. They need to be able to get themselves and any rigid ideas out of the way in order for something new and unexpected to emerge.

We really do need to stop there…

If you were tasked with re-imagining Psychotherapy or Supervision what would you do? If radical change is called for isn’t training and teaching where it needs to start? Are there ways that you’d like to challenge the status quo though your own creativity and imagination? I wonder how many of us have brilliant ideas or creative urges that remain neglected for fear of judgement, rejection, complaint, failure... or even success.

innovate

[ 'inəvert ]

Make changes to something established, especially by introducing new methods, ideas, services or products.

Thank you for reading. I hope you've enjoyed this and I would love to hear your thoughts, ideas and opinions.

Neil Turner MA UKCP BACP

Feel free to download this article here

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to view the translations.